Those two origami share a special bond

Written by Alessandro MICACCIA

1 comment

Classified in : Origami (and other arts), Slice of Science

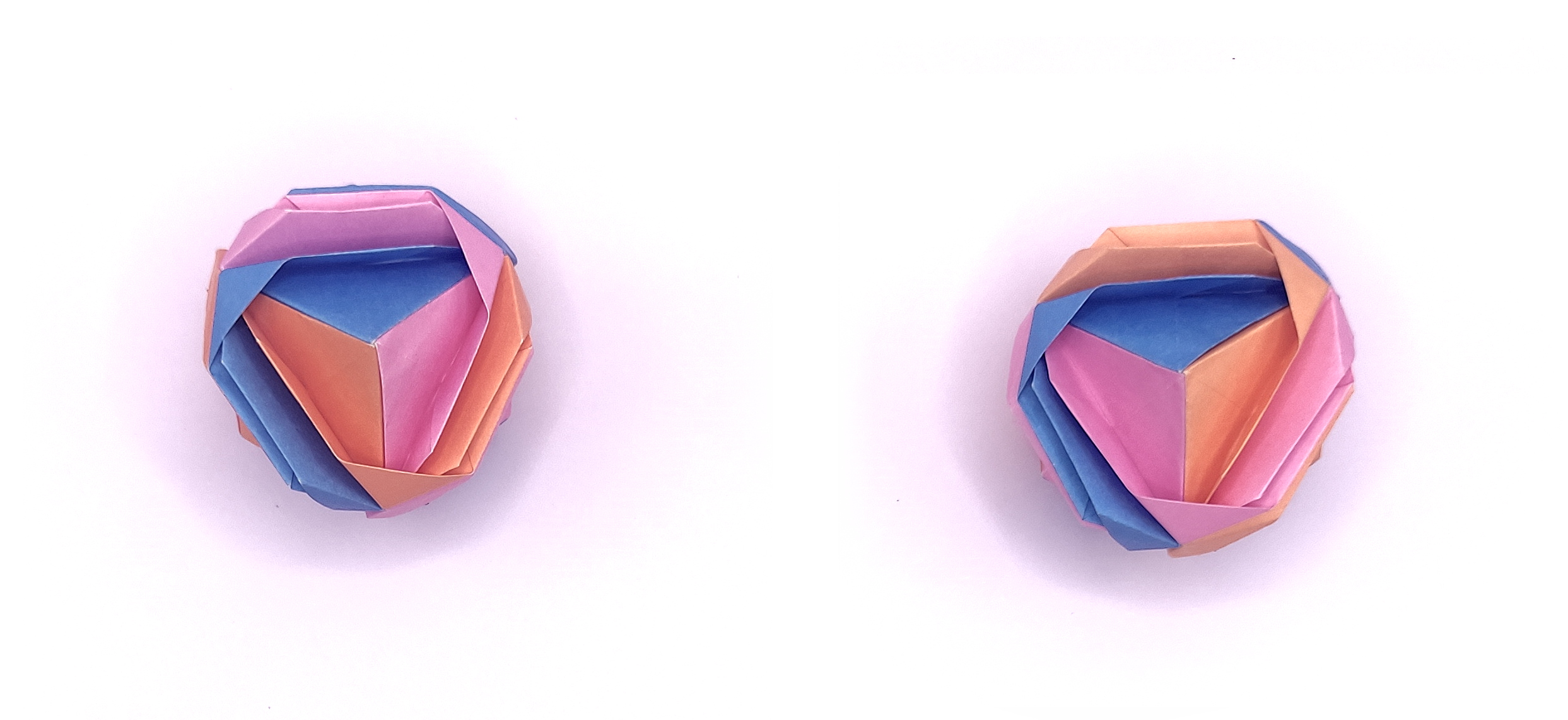

During Organic Chemistry/Stereochemistry class in my first year in college, I made a little experiment aiming to illustrate chirality and stereoisomery using the Japanese Brocade modular origami.

At that time I had recently folded the Japanese

Brocade (6 units) by Minako Ishibashi for the first time, and was happy

with how pretty it looked. Then, as I really liked the idea of chirality

and the fact you can apply this outside of chemistry, modular origami

seemed to be the best field to experiment.

Illustration of a type of chiral molecule (amino acid), with hands.

Two

molecules (or objects, especially compound objects such as modular

origami) can have the same composition (i.e. the same elements for a

molecule, the same units for an origami) and the same topology or structure, but still be distinct from each other.

Such objects may be called stereoisomers. There are two kinds of stereoisomerisms leading to different objects : diastereoisomers and enantiomers.

Enantiomers are a bit special. In order for an object to have an

enantiomer, it must have no center or plane of symmetry. This property

is called chirality. Because of this, the image such object would

have in a mirror would be a distinct object : non-superposable even

after rotation. Then if you make an object such as the image of the

initial object is, then you'll have two enantiomers in your... hands...

Ah!! Your hands are enantiomers of each other too!!

So, enantiomers

are non-superposable objects that are the image of each other in a

mirror. Other examples include sinistral and dextral snail shells, the

two valves of a mussel, or the wings (lateral petals) of a Fabaceae

(family of bean and clover) flower. (Yes there a many biology

examples... Most because of those darn bilaterians...)

And of course, it's the case of our japanese brocade...

Left to right : Helix aspera, (c) MHNT (CC BY-SA) ; Mytilus galloprovincialis, (c) stefano Merli (CC BY-NC-SA) ; Spartium junceum, Fabaceae, modified from (c) Hectonichus (CC BY-SA)

Left to right : Helix aspera, (c) MHNT (CC BY-SA) ; Mytilus galloprovincialis, (c) stefano Merli (CC BY-NC-SA) ; Spartium junceum, Fabaceae, modified from (c) Hectonichus (CC BY-SA)

But enough boring lectures!! Enjoy the origami itself!

At

first I wanted to fold just one brocade and its enantiomer. To do so I

built the second brocade by putting the units together in an opposed

fashion (change in the configuration of the units) compared to the

initial brocade. But together with my teacher (you know who you are

;) )

we realized that the two brocades were actually NOT the image of each

other in a mirror! Thus they were not enantiomers but mere

diastereoisomers...

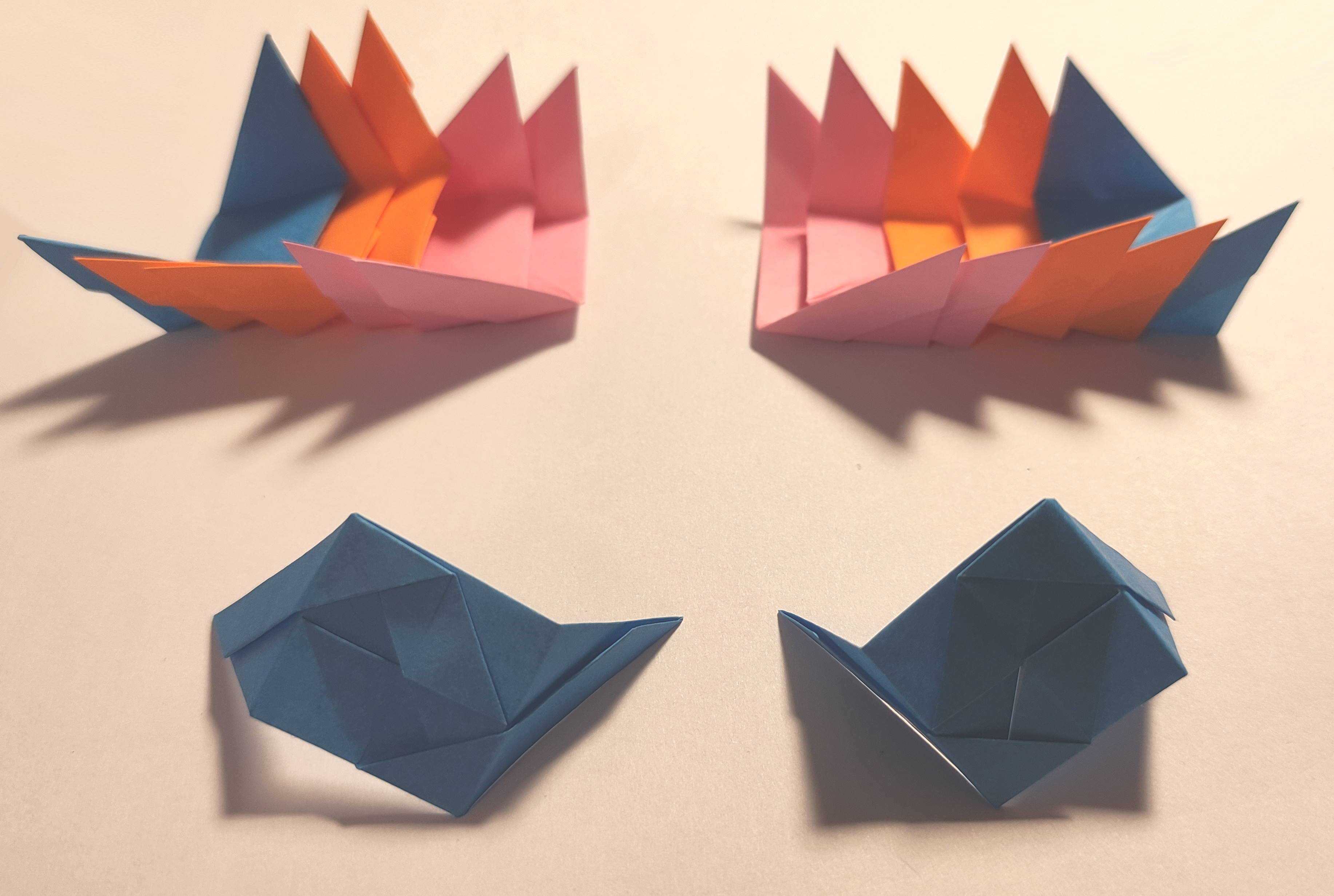

After

the shock of the realization dissipated, I quickly found the solution:

the brocade units were chiral too! So in order to build a brocade

enantiomer, you had to use the enantiomers of the initial units!

Japanese brocade units and their enantiomers

Japanese brocade units and their enantiomers

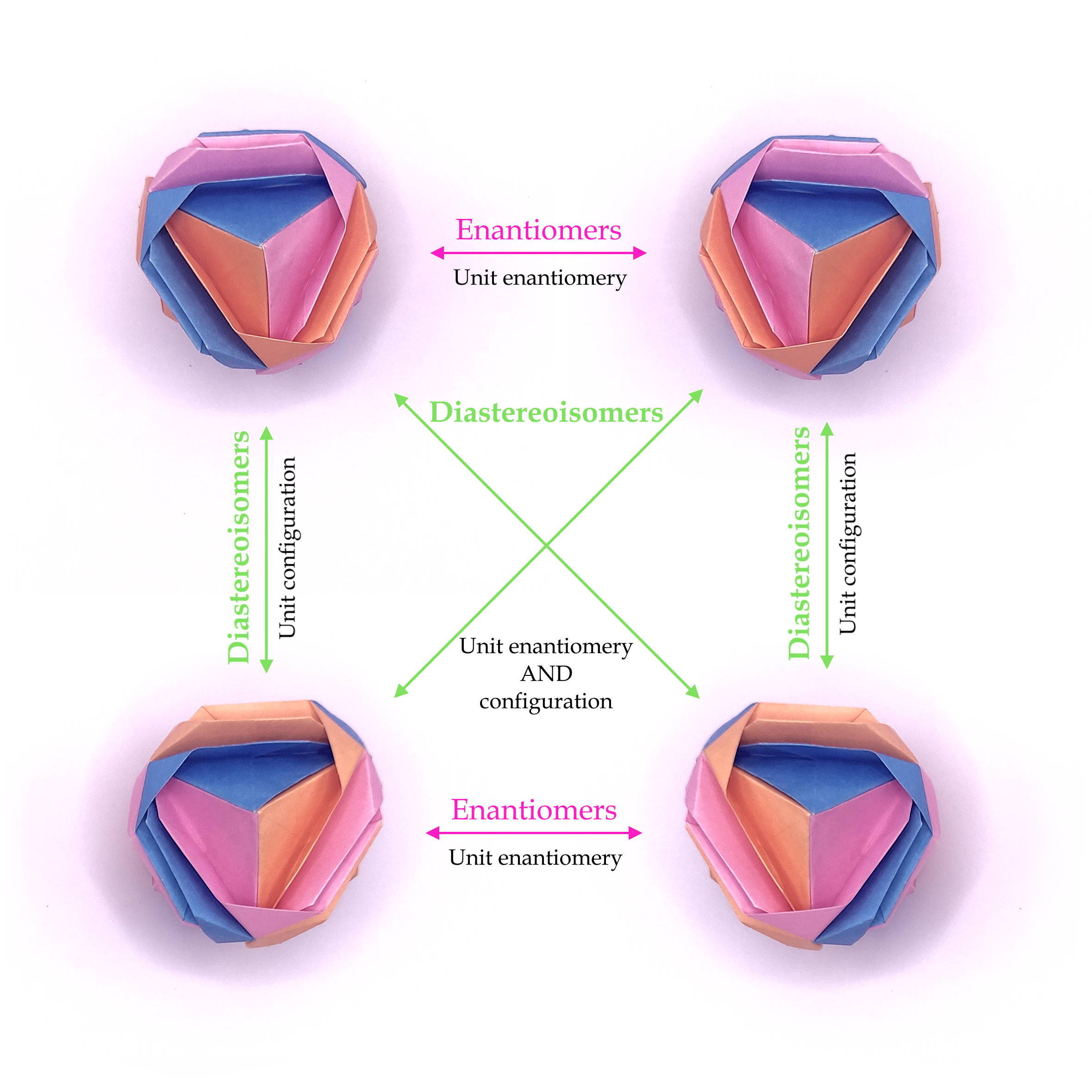

So

eventually we got to this representation, which shows how 1 single

object with the same topology can have 2 enantiomer couples!

As

a last word, I'd like to give warm greetings to my chemistry

teachers at the Université de Montpellier, who made learning organic

chemistry especially enjoyable for me.

Cheers!